|

Anti-anti-antisemite

Join Date: Nov 2004

Location: Rocky Mountains

Posts: 1,265

|

Hilton Kramer, art critic and founder of New Criterion, just another neo-con kike

Hilton Kramer, art critic and founder of New Criterion, just another neo-con kike

He's always been true to his jewishness, and although he 'pretends' to want to conserve things of value, he doesn't really know what has value--he just denounces things he doesn't like, much of which is admittedly bad.

Here he is at a function honoring him, surrounded by Jews and more Jews, and a few gentile neo-fools:

Hilton Kramer, A Man of Arts & Letters

By GARY SHAPIRO

Quote:

June 9, 2006 -- The 25th anniversary season of the New Criterion, a monthly journal devoted to the arts and intellectual life, was the occasion for a dinner in honor of its founder, Hilton Kramer.

"More than any other critic of our time - more energetically, more relentlessly, more brilliantly, more courageously - Hilton has stood out against the degradation of modernism in the arts and the symbiotic degradation of liberalism in politics and culture," Commentary magazine editor-at-large Norman Podhoretz said at the dinner.

Friends and colleagues gathered in Midtown to celebrate a magazine that recalls a time - according to the editor's note in its first issue - "when criticism was more strictly concerned to distinguish achievement from failure, to identify and uphold a standard of quality." It has sought to "speak plainly and vigorously about the problems that beset the life of the arts and the life of the mind in our society."

Mr. Podhoretz offered an anecdote that epitomized Mr. Kramer's qualities: The story goes that one night, when Hilton was still chief art critic of the New YorkTimes, he found himself seated next to Woody Allen, who asked him whether he felt embarrassed when he ran into people whose work he had attacked. "No," Hilton replied without missing a beat,"I expect them to be embarrassed for doing bad work."

Essayist Joseph Epstein sent remarks that New Criterion co-editor Roger Kimball read aloud. In the remarks, Mr. Epstein recalled the late University of Chicago sociologist Edward Shils, who had admired Mr. Kramer, once saying that what philosopher Sidney Hook [also a jew --L.D.] and Hilton Kramer had in common "was hatred of a lie."

Mr. Epstein first encountered the name Hilton Kramer in 1959 when, stationed at an army base in Little Rock, Ark., he read an attack on the New Yorker magazine that Mr. Kramer wrote in Commentary. [Back then, an exclusively jewish journal. --L.D.] He next encountered Mr. Kramer's work, "when I was associate editor of the New Leader and he was the magazine's regular art critic. I resented him slightly because, as an editor, he gave me nothing to do, so clean and finished was his copy, though on occasion I was able to remove a set of double dashes and replace them with commas, which he charitably allowed me to do."

Mr. Epstein recalled that in 1962, Mr. Kramer became an associate editor of the New Leader." His vocabulary delighted me; dressed out in his own special New England accent, it was even better. I had never heard anyone use the word 'lavish' with the same comic emphasis," he said. "When the rather philistine editor of the New Leader once asked him if every piece of art criticism had to contain the word 'oeuvre,' Hilton replied that he wasn't certain, but he could promise that every piece of his would have at least one oeuvre in it."

Speaking of the New Criterion, Judge Bork said only William F. Buckley drove him to the dictionary more frequently: "The shorter OED in two volumes is not sufficient."

Deputy director of the White House office of public liaison, Tim Goeglein, read greetings from President Bush. He also quoted American pragmatist philosopher William James in referring to Mr. Kramer's achievement: "The great use of life is to spend it for something that will outlast it."

The crowd included artists Helen Frankenthaler and Paul Resika; American Spectator editor and New York Sun columnist R. Emmett Tyrrell Jr.; Mark Steyn, a New York Sun columnist who went on to receive the Breindel Award the following evening; Midge Decter; Andre Emmerich; Commentary editor Neal Kozodoy; Hudson Institute president Herbert London; attorney and classicist William Warren; critic John Simon; a deputy managing editor at the Atlantic Monthly, Robert Messenger, formerly the deputy managing editor of The New York Sun; and Michael Grebe, president of the Bradley Foundation.

Mr. Kimball recalled the first time he met Mr. Kramer. "I was in graduate school at Yale and, doubtless because of that insalubrious influence, I ventured some cheery words about postmodern architecture. Hilton demolished that illusion quicker than you can say 'Philip Johnson,' and I never looked back."

They unveiled a portrait of Mr. Kramer, by Claude Buckley, as a token of esteem. As anyone who has seen Mr. Kramer's library knows, a book would be like bring coals to Newcastle, Mr. Kimball said.

"I've had a very lucky life," [helped along by his jew pals in the media, in academia, and in neo-con think tanks --L.D.] Mr. Kramer said, stepping to the podium. "What brings us together," he said, "is we're all on the right side."

|

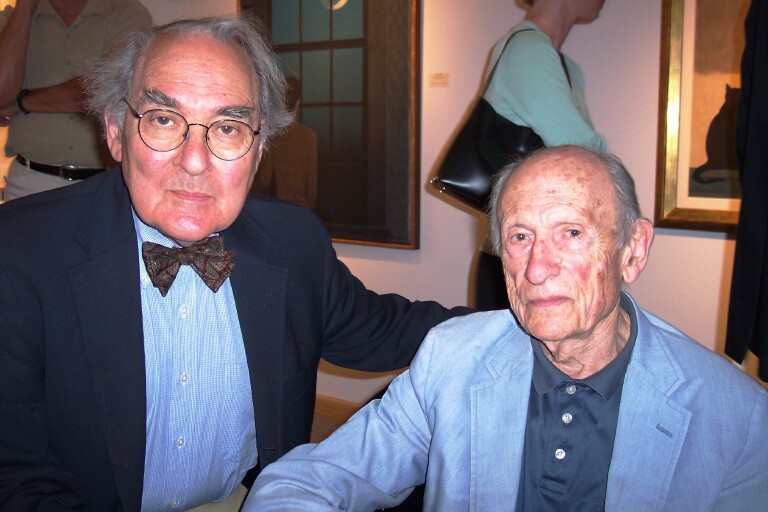

Descendent of 'Russian'-Jews, Kramer is on the left below:

ART:ISRAELI WORKS,1920-1980,SHOWN AT JEWISH MUSEUM

by Hilton Kramer

ART:ISRAELI WORKS,1920-1980,SHOWN AT JEWISH MUSEUM

by Hilton Kramer

Quote:

February 27, 1981 -- MORE than 16 years have passed since the late William C. Seitz, then a distinguished curator at the Museum of Modern Art, organized a comprehensive exhibition of contemporary Israeli art at the Jewish Museum. Called ''Art Israel,'' the show traveled extensively on the American museum circuit, and thus introduced the accomplishments of living Israeli painters and sculptors to the American art public.

Now the Jewish Museum has returned to the subject with an exhibition called ''Artists of Israel: 1920-80.'' Organized by the museum's chief curator, Susan Tumarkin Goodman, this show attempts to give us a somewhat wider perspective on the history of modern Israeli art. While including some of the artists whose work appeared in the Seitz exhibition, it also focuses on the work of the older generation, artists who started in the 1920's. At the same time it brings us up to date on recent and current developments.

The result is an exhibition that is often of more historical than of purely artistic interest. There are, to be sure, some very interesting and accomplished painters represented in this exhibition - among others, Yosef Zaritsky, Yeheskel Streichman, Avigdor Stematsky, Michael Gross, Joshua Neustein, Avigdor Arikha and Moshe Kupferman. And there are two good sculptors - Yitzhak Danziger and Yehiel Shemi. But much of the art that we see in this survey is, sad to say, provincial in conception and undistinguished in execution. On the basis of this exhibition, at least, one is compelled to observe that the country [Israel] has not yet produced a single artist in the master class.

Given the very difficult conditions under which Israeli artists have been obliged to live and work, [unlike, say, the lavish conditions in which Palestinian artists work and live... --L.D.] it is something of a miracle, of course, that they have accomplished as much as they have. Art thrives, after all, on vital artistic traditions, and as far as the visual arts are concerned, these have apparently been slow in establishing themselves in Israel. Artists have often had to look elsewhere - to Paris, New York and other international centers - for inspiration and impetus, and ideas imported from abroad have not always been clearly understood or assimilated with the requisite taste. For artists who have chosen to live and work abroad, there are inevitably other problems--most notably, the problem of identity....

|

BOOK REVIEW: The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy. By Murray Friedman. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. vi, 303 pp. $29.00, ISBN 0-521-83656-5.)

by Kevin J. Smant

Quote:

This is a well-researched, timely book delving into the history of "neoconservatives" and their impact on U.S. policy and culture. Murray Friedman argues that Jewish intellectuals played an important role in the emergence of neoconservatism, which has in turn impacted American conservatism as a whole. Thinkers such as Irving Kristol and Norman Podhoretz have played pivotal roles in shaping a more conservative direction for American domestic and foreign policy since the 1960s. How did this happen?

Someone once remarked that a neoconservative was a liberal "mugged by reality." Friedman does not greatly depart from this thesis, but he adds some crucial elements to it. He tells the familiar story of how many future neoconservatives began as members of the New York "cosmopolitan" Left in the 1930s and 1940s. But Friedman also stresses that this is not the sum total of the movement's origins—also important were the surprising (and heretofore often ignored) numbers of Jewish conservatives active before and immediately after World War II. There were libertarians such as Ayn Rand and Frank Chodorov and members of the National Review magazine circle such as Frank Meyer and Will Herberg. Some of the free-marketeers at the University of Chicago were Jewish intellectuals.

Such tendencies prepared the way for the later coming of neoconservatism; Friedman nicely shows the connections between this body of work and later neoconservatism. From here, the story becomes a familiar one, though it is thoughtfully and thoroughly told: The antiwar radicalism of the 1960s, along with perceived anti-American and anti-Jewish feeling among African American radicals, turned off thinkers such as Kristol, Podhoretz, and others; Kristol then created the journal the Public Interest, and Podhoretz moved Commentary to the right, while the drift of Democrats and even some Republicans toward détente with the Soviet Union led many neoconservatives to fear that the United States was losing the Cold War.

This intellectual path placed most neoconservatives in Ronald Reagan's camp; their support, and his victory over Jimmy Carter in 1980, eventually got neocons such as Jeane J. Kirkpatrick, Elliott Abrams, and Richard Perle key positions in the Reagan administration and influenced U.S. policy, from arms-control negotiations to Nicaragua to the Strategic Defense Initiative. Neoconservative influence has thus remained strong up to the present, from Gertrude Himmelfarb and Hilton Kramer's influence on history, multiculturalism, and literature to the impact of Paul Wolfowitz and the Weekly Standard on the war in Iraq. There can be no question of neoconservatives' importance in American political and intellectual history over the past sixty years. After World War II, they were some of the first to point out weaknesses in America's welfare policies, and they were influential in pushing American foreign policy toward a tough stance on the Soviet Union. This work is not merely a celebration of neoconservatism; Friedman is at times critical, for example, questioning whether neoconservatives fully appreciated the plight of America's poor.

On the whole, this is an important contribution to the field and would be appropriate for graduate and upper-level undergraduate courses. It is based mainly on secondary sources, interviews, and neconservatives' public writings. One wishes that this work could have included more archival research. But that is not Friedman's fault: most of his subjects are still alive and thus their archives are not yet open to researchers. Soon they will be. We will learn more then. Friedman has, however, given later historians a valuable beginning point.

|

I found an interesting review of Kramer's book "Twilight of the Intellectuals" at Amazon:

Quote:

Do these people matter?, January 12, 2004 By David H Miller "rothbardianphysicist"

In his introduction, Hilton Kramer declares himself to be a "partisan" of artistic "modernism" and a "liberal anti-Communist." These essays are, then, a critique of twentieth-century Western leftist/modernist intellectuals by one of their own. Much of the book is taken up with denunciations of the Stalinism which was rampant among Western intellectuals in the 1930s and '40s. Kramer is here generally on target: there is no longer any honest doubt that Alger Hiss was a Soviet spy or that Lillian Hellman was a pathologically dishonest Stalinist stooge.

Even towards those intellectuals who were not tools of Stalinism, Kramer is unsparing. Although he seems in some ways to admire Mary McCarthy, he declares, "Mary McCarthy's politics were like her sex life -- promiscuous and unprincipled, more a question of opportunity than of commitment or belief."

The greater interest of the book lies in the hints Kramer offers the reader as to what went wrong with the whole twentieth-century intellectual enterprise. The author is never able to draw these hints together into a coherent explanation, perhaps because he himself continues to share the basic premises underlying the twentieth-century intellectual catastrophe.

Ernest Gellner once suggested that the rise of Anglo-American "linguistic philosophy" in the twentieth century was a consequence of verbalist intellectuals, having been displaced by modern science, trying to create for themselves a new niche which would justify their own skills of verbal manipulation. ["Verbalist intellectual" = jew  --L.D.] --L.D.]

The same analysis explains the intellectuals' attraction to both Marxism and "modernism."

In discussing modern art, Kramer refers approvingly to the "culture of modernism, with its 'difficult' texts requiring lengthy and laborious study..." He specifically lavishes praise on Clement Greenberg, one of the most influential of modernist art critics.

Why it is that "'difficult' texts requiring lengthy and laborious study..." are per se a good thing, Kramer does not say. The answer of course is that such texts provide a raison d'etre for verbalist intellectuals who possess no actual knowledge or any useful expertise. Tom Wolfe, in "The Painted Word," developed this point in a brutally brilliant (and hilarious) attack on artistic modernism, focusing specifically on Kramer's hero Clem Greenberg: modern art is nothing but illustrations for the insanely convoluted and incomprehensible scribblings of self-important twentieth-century verbalist intellectuals.

Similarly, Marxism assigns to intellectuals a far more exalted status than they would otherwise appear to deserve: whatever the ultimate metaphysical role of the proletariat, it is, in practice, the intellectuals, not the poor workers, who have grasped the Marxian dynamics of history. It is therefore the intellectuals who are fitted to run the show under Marxism.

That modernism and Marxism would appeal to intellectuals is therefore obvious. But does it matter? How could a small band of discontented intellectuals affect society at large?

Kramer again offers us hints of how relatively small numbers of leftist/modernist intellectuals spread their influence throughout American society. Kramer explains that Stalinists :[] insinuated themselves into such "capitalist" institutions as Time magazine, the New York Times, and the universities, and, in some cases, received monetary subsidies from the Soviet Union.

The Soviets never accepted modern art, so Soviet funds were not available to fund artistic modernism. Curiously, funding for political leftists who espoused artistic modernism was provided by the American CIA! Kramer explains in some detail that the CIA-funded "Congress for Cultural Freedom" exhibited an "over dependence on the political Left as the intellectual mainstay of the Congress..." He adds approvingly, and not surprisingly given his own leftist leanings, that this "may indeed have been necessary given the realities of the moment..."

The most bizarrely fascinating essay in the book discusses the famous "Bloomsbury group" -- which included Vrginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey, John Maynard Keynes, etc. The phrase "moral decadence" is not adequate to capture the picture Kramer paints.

For example, Vanessa Bell, sister of Vrigina Woolf and the pivotal figure in the group, although married to Clive Bell, had a child by Duncan Grant, whose own real romantic interest was not Vanessa Bell but his own gay lover, David Garnett. In a final weird twist, the gay lover Garnett ended up marrying the illegitimate daughter when she matured.

The Bloomsburyites, who prided themselves on their sexual openness and lack of hypocrisy, kept the whole strange matter secret from the unfortunate girl who thought her biological father was Clive Bell.

In the early twentieth century, the Bloomsbury ethos was the preserve of a tiny group of upper-class aesthetes -- although Bloomsbury member John Maynard Keynes did succeed in selling Western governments upon an economic theory built upon the take-no-thought-for-the-morrow Bloomsbury ethos, with a resulting near collapse in the value of Western currencies.

But that ethos has now trickled down widely to the middle and working class in America, as is illustrated, for example, by the infamous Jerry Springer television program: Springer is a twenty-first century pop-culture version of the Bloomsbury group.

As an old-fashioned liberal (what is nowadays called a "neoconservative"), Hilton Kramer is an apologist for the basic political, social, and cultural institutions of the twentieth century. While he deplores much of what his intellectual colleagues have done to our society, he lacks the vantage point to see that the early twentieth century liberal "advances" in the power of government, the structure of education, etc. made this destruction possible.

That Kramer himself is now often dubbed a conservative, rather than, as he himself confesses in his introduction, a liberal, is a sign of the lack of any real conservative alternative or response to the catastrophic social and intellectual decline that constituted the twentieth century.

Nonetheless, if Kramer can offer no cure, "Twilight of the Intellectuals" is a fascinating and readable look at some of those intellectuals who helped cause the illnesses from which we and our society now suffer.

|

|